Article

While battlefield victories and a renewed electoral mandate have defined recent days, government officials have increasingly acknowledged the severe domestic toll imposed by years of barbarian occupation and sustained fighting across the United Kingdom.

The timing of this reassessment was deliberate. Within hours of securing re-election, the Prime Minister convened senior ministers, military commanders, and economic planners to address what officials described as “the next and more dangerous phase of the war”—the survival of British civilians during a prolonged period of instability.

Government sources confirmed that the Prime Minister viewed the electoral victory not as an endpoint, but as a mandate to act decisively beyond the battlefield. With national unity reaffirmed at the ballot box, attention shifted from territorial reclamation to the protection of food supplies, labour stability, and the material foundations of everyday life.

“Winning wars means nothing if your people cannot endure what follows,” one senior aide said. “This was the first priority after the vote.”

The Domestic Cost of Occupation

According to assessments released by the Ministry of Supply and Labour, prolonged conflict has significantly disrupted the national workforce. Large numbers of labourers were displaced as fighting moved through rural and industrial regions, while repeated sabotage and scorched-earth tactics damaged farmland, transport corridors, and storage facilities. Entire harvests were lost in contested zones, machinery destroyed, and livestock scattered or slaughtered during the fighting.

Farmers in affected regions reported successive seasons of reduced output, with some areas rendered temporarily unusable due to unexploded ordnance, soil degradation, and collapsed infrastructure. Supply chains that once moved grain, meat, and fuel efficiently across the country fractured under the strain of conflict, creating bottlenecks and shortages in key regions.

The result, officials warned, was not famine—but vulnerability.

“The war has been fought on our soil,” one senior official stated. “And war always leaves scars on production before it leaves scars on maps.”

Briefings circulated within Whitehall following the election warned that without immediate intervention, food insecurity could become the defining threat of the next phase of the conflict—capable of undermining morale, industrial output, and social cohesion. Reconstruction would continue, officials said, but survival planning could no longer be reactive.

Securing the Lifelines of the Nation

It was against this backdrop that the Prime Minister approved one of the first major policy decisions of his renewed term: a strategic outward expansion of Britain’s resource security doctrine.

Cabinet approval was fast-tracked under emergency authority. The rationale was clear. Caring for the population required not only rebuilding at home, but securing reliable external sources of food and raw materials beyond the reach of instability.

It was within this context that Britain announced the launch of a campaign in Greenland.

By the time British forces mobilised, Greenland had effectively ceased to exist as a functioning political entity. Intelligence reports confirmed that the region had been overrun by barbarian forces exploiting its isolation, limited defences, and fractured administration. Ports fell silent, production collapsed, and civilian populations were left exposed, cut off from supply and protection.

For British planners, Greenland represented both an urgent crisis and a strategic necessity. Britain required grain and food security to sustain its people through reconstruction and ongoing war. Greenland’s agricultural potential, production capacity, and geographic position offered a solution—if stabilised.

“This is not extraction for profit,” one Reclaim Britannia official stated. “It is provisioning for survival.”

From War Economy to Sustained Power

Military units assigned to the Greenland operation were drawn largely from forces no longer required in domestic stabilisation roles. Defence sources stressed that the campaign was designed to be limited, focused, and decisive.

The objective was twofold: to restore order and protection to Greenland’s civilian population, and to establish secure production zones capable of supplying Britain without dependence on volatile external markets.

Analysts note that the move aligns closely with Reclaim Britannia’s broader doctrine: a state that does not merely defend its borders, but actively secures the material foundations of its people’s well-being.

Critics warn that the operation risks widening Britain’s commitments at a sensitive moment. Supporters counter that history has repeatedly demonstrated the dangers of resource insecurity during wartime.

The government appears unmoved.

“With our territory reclaimed and our mandate confirmed,” the Prime Minister stated, “our responsibility now is to ensure that no British family goes hungry—and that no northern people are left unprotected because we hesitated.”

Shared Blood, Shared Responsibility

Officials were careful to stress that the Greenland campaign was not framed solely in terms of resources.

Government statements invoked deep historical ties between Britain and the northern Atlantic world, arguing that intervention carried a moral as well as strategic dimension. Britain and Greenland, officials noted, share centuries of intertwined history through trade, migration, and empire.

Historians advising the government pointed to the legacy of the North Sea Empire, when Norse kingdoms bound England, Denmark, and the wider North Atlantic into a shared political and cultural sphere. Viking settlers left enduring marks on English language, law, and identity—connections that persisted long after the age of conquest.

“Our peoples have crossed these waters for centuries,” one briefing noted. “Shared blood, shared history, shared survival.”

Allowing Greenland’s population to remain under barbarian control, officials argued, would not only endanger Britain’s supply security but abandon a people historically linked to the British Isles.

A Swift Campaign by Design

Military officials emphasised that the Greenland campaign unfolded very differently from the hard-fought operations seen elsewhere.

Intelligence assessments prior to deployment indicated that barbarian rebel elements in the region lacked both the experience and infrastructure necessary to sustain prolonged resistance. Unlike forces encountered in the British Isles and Ireland, these groups were neither battle-hardened nor centrally organised.

Greenland’s harsh terrain, sparse population, and isolated global position limited access to advanced weaponry, fortified supply networks, and coordinated command structures. Resistance was fragmented and largely defensive.

As a result, fighting concluded rapidly.

British forces prioritised speed, precision, and containment over overwhelming force. Specialised units secured ports, airstrips, transport corridors, and agricultural zones before significant damage could occur. Rules of engagement were deliberately restrictive, aimed at preventing sabotage and preserving critical assets.

Losses on both sides were described as minimal.

“This campaign was about protection as much as control,” one defence official said. “The aim was to hold the land intact—not to fight over ruins.”

Securing Resources, Preserving Supply

The rapid conclusion of hostilities proved central to the government’s broader strategy. Agricultural infrastructure—including grain fields, storage facilities, and transport links—was secured largely undamaged, allowing production to begin almost immediately under British oversight.

Analysts describe the outcome as evidence of an evolving British doctrine: operations conducted not solely for victory, but for continuity. In Greenland, success was measured less by enemy losses than by intact fields, functioning supply lines, and civilian stability.

With barbarian resistance neutralised and strategic positions secured, Britain now faces the task of integrating Greenland’s production zones into its wider supply network—an effort officials describe as essential to sustaining both the British population and Greenland’s recovery.

In contrast to earlier campaigns marked by prolonged fighting and heavy disruption, Greenland is being held up as a model of what the government calls “stabilisation-first warfare”: decisive, contained, and focused on sustaining life beyond the battlefield.

As Britain transitions from internal reclamation to external consolidation, the Greenland campaign marks a new phase—one in which victory is measured not only in territory held, but in bread on tables, people protected, and stability secured.

An Unfinished War

Despite battlefield successes and expanding control abroad, officials are careful to stress that the war in Ireland is not yet concluded. However negotiations are underway.

Among analysts and the public alike, debate continues. Some argue the government’s posture reflects overreach—an ambition stretching Britain’s commitments at a critical moment. Others interpret the stance as a calculated display of confidence, rooted in battlefield leverage and a belief that negotiations will ultimately formalise gains already secured by force.

For now, the government maintains that strength at the table is inseparable from strength on the ground. Whether this confidence proves justified remains to be seen.

Previous article:

Leadership on Trial (7 days ago)

Next article:

Negotiations Collapse (6 days ago)

About the game:

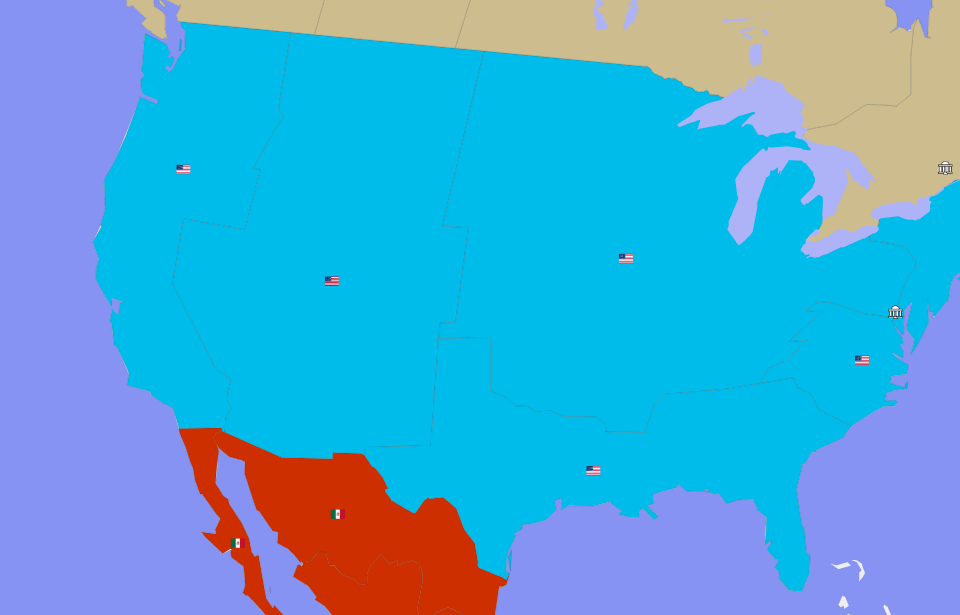

USA as a world power? In E-Sim it is possible!

In E-Sim we have a huge, living world, which is a mirror copy of the Earth. Well, maybe not completely mirrored, because the balance of power in this virtual world looks a bit different than in real life. In E-Sim, USA does not have to be a world superpower, It can be efficiently managed as a much smaller country that has entrepreneurial citizens that support it's foundation. Everything depends on the players themselves and how they decide to shape the political map of the game.

Work for the good of your country and see it rise to an empire.

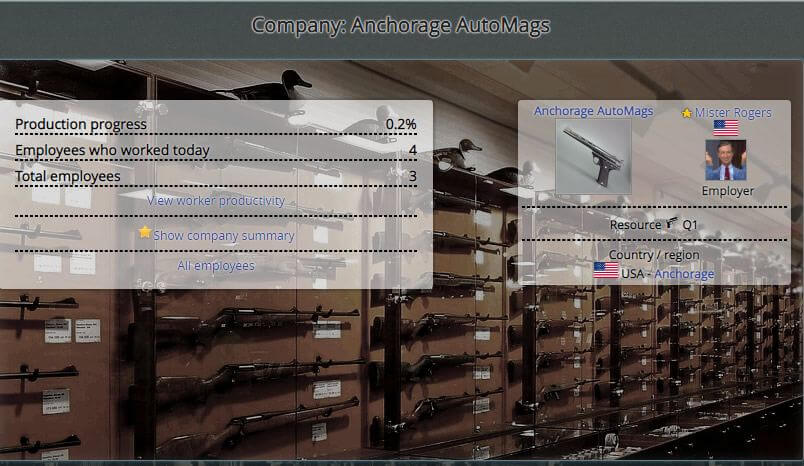

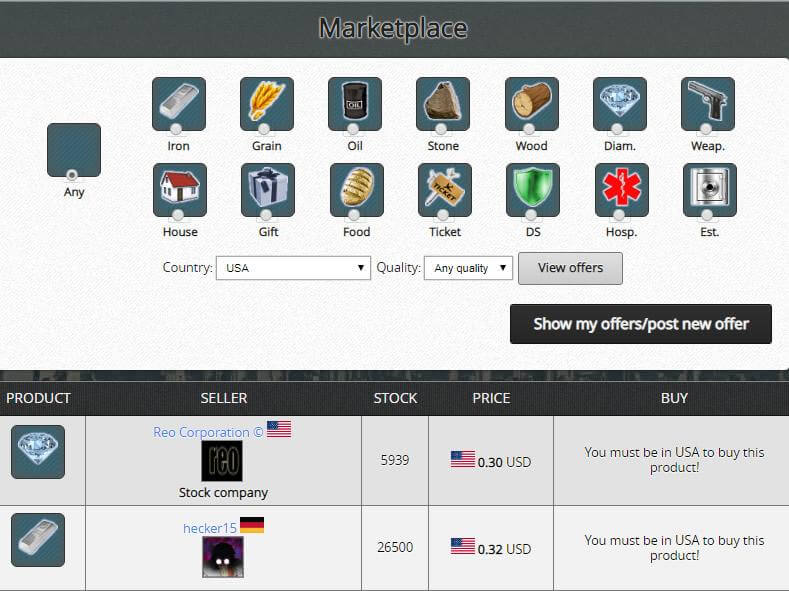

Activities in this game are divided into several modules. First is the economy as a citizen in a country of your choice you must work to earn money, which you will get to spend for example, on food or purchase of weapons which are critical for your progress as a fighter. You will work in either private companies which are owned by players or government companies which are owned by the state. After progressing in the game you will finally get the opportunity to set up your own business and hire other players. If it prospers, we can even change it into a joint-stock company and enter the stock market and get even more money in this way.

In E-Sim, international wars are nothing out of the ordinary.

Become an influential politician.

The second module is a politics. Just like in real life politics in E-Sim are an extremely powerful tool that can be used for your own purposes. From time to time there are elections in the game in which you will not only vote, but also have the ability to run for the head of the party you're in. You can also apply for congress, where once elected you will be given the right to vote on laws proposed by your fellow congress members or your president and propose laws yourself. Voting on laws is important for your country as it can shape the lives of those around you. You can also try to become the head of a given party, and even take part in presidential elections and decide on the shape of the foreign policy of a given state (for example, who to declare war on). Career in politics is obviously not easy and in order to succeed in it, you have to have a good plan and compete for the votes of voters.

You can go bankrupt or become a rich man while playing the stock market.

The international war.

The last and probably the most important module is military. In E-Sim, countries are constantly fighting each other for control over territories which in return grant them access to more valuable raw materials. For this purpose, they form alliances, they fight international wars, but they also have to deal with, for example, uprisings in conquered countries or civil wars, which may explode on their territory. You can also take part in these clashes, although you are also given the opportunity to lead a life as a pacifist who focuses on other activities in the game (for example, running a successful newspaper or selling products).

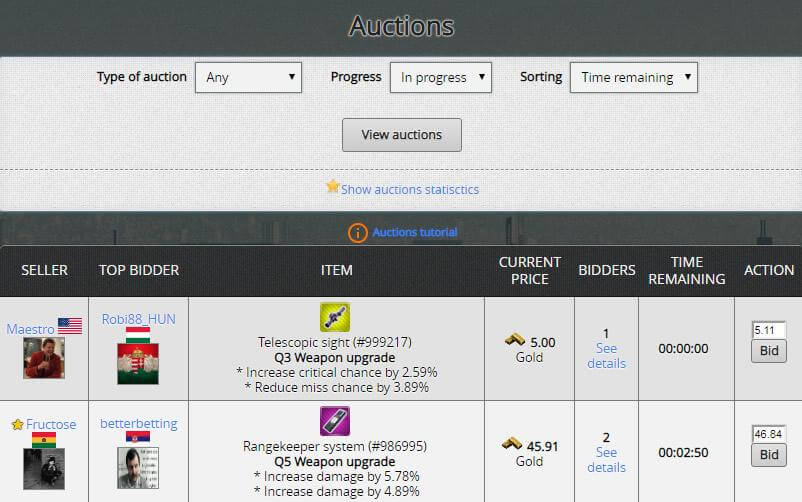

At the auction you can sell or buy your dream inventory.

E-Sim is a unique browser game. It's creators ensured realistic representation of the mechanisms present in the real world and gave all power to the players who shape the image of the virtual Earth according to their own. So come and join them and help your country achieve its full potential.

Invest, produce and sell - be an entrepreneur in E-Sim.

Take part in numerous events for the E-Sim community.